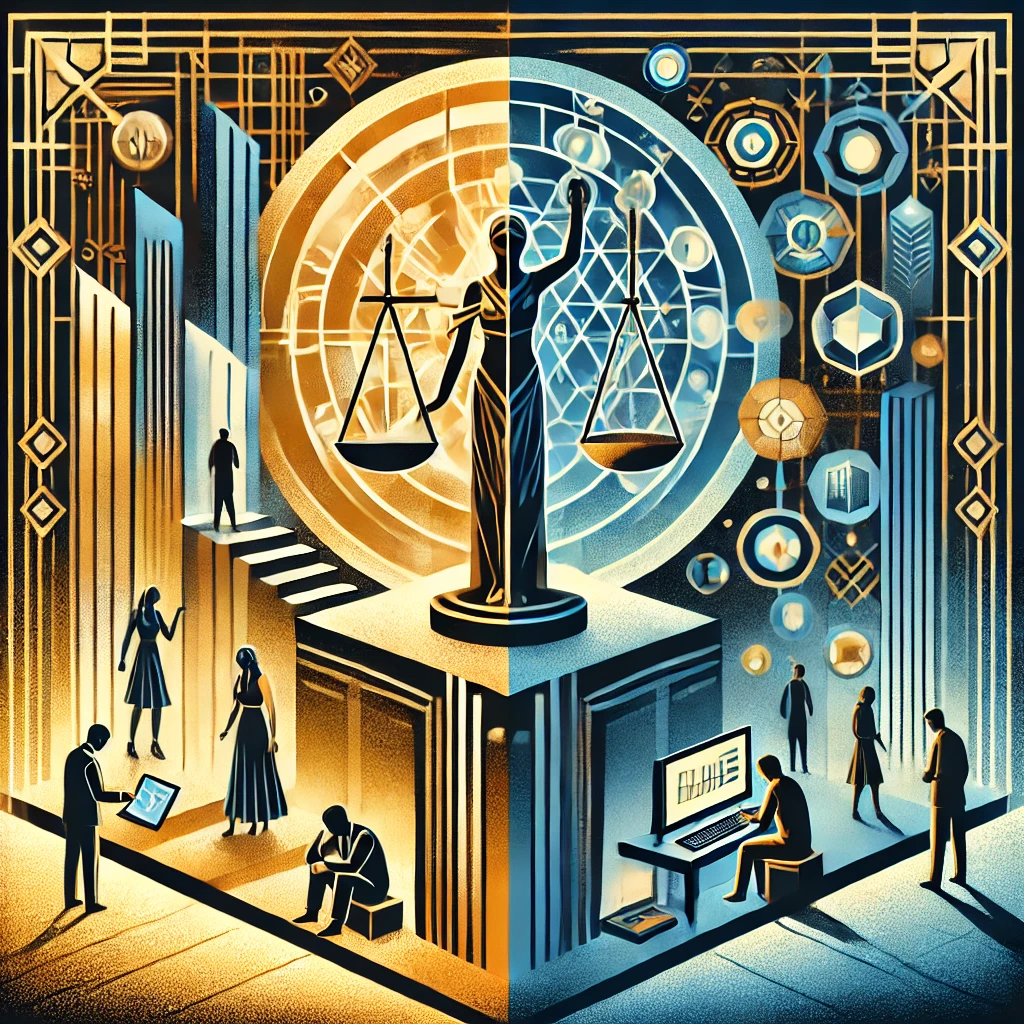

For the first time since the Bush-era stem cell debates, reproductive technology has taken center stage in American politics. An Alabama Supreme Court decision in February granted parents the right to legal recourse after their embryos were destroyed due to neglect by a fertility clinic, sparking a national debate about the laws governing in vitro fertilization, the technology used to create the embryos.

The court ruled that parents have the right to sue under Alabama’s wrongful-death statute, thus considering frozen embryos persons, and not property, for this purpose. Within days, fertility clinics began pausing their IVF services, and politicians and commentators across the country warned that the court’s decision could prohibit people from accessing infertility care. Notably, the decision did not prohibit IVF, nor did it prohibit the destruction of embryos.

The public confusion that has arisen in the wake of the Alabama decision is about how the IVF industry can be expected to operate in a state that considers embryos persons for the purpose of a wrongful-death lawsuit. In vitro fertilization often involves the destruction of embryonic life. This may happen intentionally, for example if parents decide to discard their embryos, or through neglect, like whcccccCVVvven a freezer tank fails. Clinics also routinely create a surplus of embryos for a given IVF cycle to test them for the “best” genetic profile or to offer parents a choice of preferred sex or physical features.

The confusion brings to light a fundamental conflict in how IVF has been regulated, and how it hasn’t. The effect of existing law for decades has been to protect the consumer — the parents — not the human life being created — the children. In the Alabama decision, these two aims have suddenly collided: in order to protect the parents’ rights to their embryos, the embryos were declared to have the same protections as any other children.

Regardless of what one thinks about IVF, a practice that creates and selects human life should be subject to the highest moral standards. For better and worse, lawmakers are beginning to pay attention to an industry that has long needed better oversight.